DarkMedia Interviews A.J. Hartley:

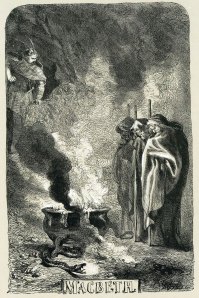

Shakespeare’s Macbeth is frequently referred to as “The Scottish Play” or “The Scottish Tragedy” by those who believe the name itself invokes a curse when spoken inside a theatre. Its legend of death and disaster goes all the way back to 1606, when Shakespeare himself was forced to take the stage after an actor fell suddenly ill — with less than favorable results. To this day, more than any other Shakespearean tragedy, Macbeth is a play that inspires both awe and fear for actors and spectators alike.

Macbeth: A Novel is a work which not only strives to bring new depth to this infamous tale, but succeeds brilliantly in doing it. Released as an audiobook featuring the always incredible Tony Award winning actor Alan Cumming, this is truly a story for everyone. Whether you’ve read Macbeth a hundred times over, or never at all, you’ll find yourself drawn into a rich, dark world of magic, ambition, and the tragedy of a man who is seldom ever seen in such a sympathetic light.

DarkMedia was fortunate enough to interview New York Times bestselling author, and Shakespeare professor, A.J. Hartley about Macbeth: The Novel, Macbeth the play, and Macbeth the man.

DarkMedia was fortunate enough to interview New York Times bestselling author, and Shakespeare professor, A.J. Hartley about Macbeth: The Novel, Macbeth the play, and Macbeth the man.

Macbeth truly does seem to be the perfect play for this kind of adaptation; the skeleton of the story is so dynamic and rich, while still leaving enough room for an incredible amount of freedom for interpretation and creativity. Did you know right away this was “the one”, or were there other plays you considered adapting before settling on Macbeth?

We never seriously considered another play, though we have had conversations about possibly doing another in the future. I had written an essay on Macbeth for the 100 Must Read Thrillers collection and my co-author, David Hewson, and I were thrown together by virtue of the alphabet during a mass signing session at Thrillerfest in July 2010. Our conversation was specific to this play—or rather to this story—and its suitability for a kind of historical thriller.

- Death of Lady Macbeth by Rossetti Dante

Being not only an author, but a veteran of the theatre, do you believe Macbeth is cursed? Did you have any strange experiences while writing or producing the audiobook that would compare to the stories that invariably come from those who produce and perform in the play itself? Or does the stigma truly die when the work is outside of the theatre itself?

I kind of do think the play is cursed, because there’s so much about it (regicide, witchcraft, killing children) which is unsettling on the stage. Also any play with sword fights in it can get all kinds of scary when things go wrong. But I actually think that the hardest thing about the play Shakespeare wrote is the language, some of which is willfully, deliberately difficult as characters try to articulate things which should not be said: If it were done when ‘tis done, then ‘twere well it were done quickly. If the assassination could trammel up the consequence and catch with his surcease success… Very tricky stuff for an actor. Our version dodges that particular bullet because we use modern prose. Maybe that’s why we didn’t experience anything too odd or frightening as we worked on it, except, of course, the nagging dread that the purists would put us on trial and have us ritually executed.

How old were you when you were first introduced to Shakespeare? Which play was your first?

I remember reading Shakespeare in high school (Romeo and Juliet, predictably) but I didn’t really connect to it till I saw it on stage. My father took my brother and I to see a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream done by the (then new) innovative company Cheek by Jowl. It was electrifying. Then when I was an undergraduate in Manchester I became obsessed with the Royal Exchange Theatre who staged some wonderful Shakespeare while I was there. The kinds of stuff where you come out of As You Like It convinced you’re in love with Rosalind.

How did you and (co-author) David Hewson go about your research for Macbeth: A Novel? And how long was the research process before you began to write? Was there a lot of travel involved?

We divided up the research. I knew the play and its scholarly context pretty thoroughly so I got to focus on fun stuff like history Shakespeare hadn’t used, weapon types and so on. David, who was in the UK, hopped on a plane to Scotland and spent a week wandering the highlands, sending me photographs. That was really helpful and instructive. But all this happened pretty much as we were writing. We didn’t really have a separate research period before hand. Since we already had the skeleton of the story from Shakespeare, we just dived in.

- Orson Welles in the title role in his 1948 adaptation of Macbeth.

Given that every modern production of Shakespeare’s work is technically “adaptation”, how do you feel about the films and plays that have brought the characters into the modern world? Was this always a historical piece for you, or did you ever consider a modern adaptation?

I love seeing productions (film or stage) of Shakespeare because I go in expecting to see something new, to hear a line I’ve barely noticed before become resonant or important. I’m utterly committed to the idea that production is the creation of a new artistic product rather than the mere transmission of one that already existed (the script).

That said, we wanted to retain the feel of the original, even though we modernized the language in which the story was told, partly because I don’t think there are direct modern analogues for things like kingship which are so central to the story. If we’d done Macbeth as a drug baron, or a CEO, I think the familiar story would have become increasingly irrelevant, so that we would have found ourselves wanting to jettison it entirely. The challenge in my mind was always to do something new, interesting, even surprising, with a story most readers would already know.

With very few exceptions, you chose not to include the dialogue from the play. What inspired that decision, and why did you include the lines that you did?

We wanted to make the story feel fresh. On stage, famous speeches are terrifying for actors because they have to stop the audience sliding out of the play and back into memories of school or whatever. Sometimes you can see the audience mouthing the words along with the actor. Nightmare! We really wanted to keep the story working at the level of character, not allowing it to slide back into “famous literature.” That would have really defeated the purpose and, I think, would have been cowardly.

Even so, there are a couple of moments when the listener who knows the play will detect the echo of a Shakespearean line, and there are a few (only a few) that survive intact. They should feel a little different from the original because of the context, but they were just too good to lose outright. He could turn a phrase, could Will.

- Lady Macbeth Seizing the Daggars by Henry Fuseli

In the age-old Macbeth debate regarding “Fate versus Free Will”, where do you stand? Is he a victim of his own choices, inspired by ruthless ambition? Or is he simply a pawn of fate, doomed from the beginning? Is it really that simple?

No, I don’t think Macbeth is fated to do anything. He certainly isn’t in our version and David and I talked about this early on. If he’s fated, then he’s not in control of his own actions, and I can’t think of anything less interesting than a protagonist who has no agency. More to the point, if he’s not in control of his own actions, he also can’t be held accountable for them. If the decisions are his (and his wife’s) then so are the moral implications. That’s important. To make him a pawn of fate is to absolve him of responsibility, and we didn’t want to do that, even though we wanted people to like, even respect, him.

Is Macbeth a sympathetic character?

See above: Yes. We had no interest in drawing a monster. We wanted to see a good, patriotic man, and watch him as he makes bad choices, and things get away from him. One of the things which is hard about the play on stage is that he’s tough to really like because we don’t get chance to know him before he starts doing things that alienate the audience (who are pretty much hard wired from experience to think he’s a butcher before the show even starts). We want people to weep for him.

- Macbeth visits the Three Witches by Sir John Gilbert

What role do you see the witches playing in the tragedy of Macbeth? Did you and David do extensive research into the practice of witchcraft as well, or was your interpretation of the Weird Sisters based more on imagination?

David did explore aspects of Celtic festival and ritual practice but our witches are really the products of our own (twisted) imaginations as prompted by Shakespeare. For instance, the play is ambiguous on what they look like, presenting them as bearded women. They are slippery, tough to categorize, and tap into the play’s anxieties about what constitutes masculinity and femininity. We pushed that in a different direction, creating three ‘witches’ who are all quite different, but all unsettling oddities who resist easy categorization. One is very young but sexual, one is very old and goes about on crutches like a crab, one is large and mannish. The nature of their supernatural power is tricky, but I’ll leave the determination of that to the listener.

How did Alan Cumming come to be involved in the project? And what was it like the first time you heard his rendition of the book?

Audible approached him. David and I were kept in the loop, but he was their choice. I was ecstatic when I heard he was doing it. He has a real edge that I think the project wanted, so that people wouldn’t think it was some dusty retelling of the Bard. He also has the range to play a huge cast of characters.

Do you see Macbeth: A Novel functioning as a companion to the play itself, or is a piece you’d like to see stand completely on its own?

Of course there’s a sense in which it can’t be separated from the play and (as an academic) there’s a sense that it is kind of response to the play like a critical essay which draws attention to some of the play’s features and makes an argument about it. But we really wanted this to stand alone, and I think its success in that area is that you don’t need to know anything at all about the play to enjoy our version.

Do you have a favorite Shakespearean play? Is this it?

It varies. The Winter’s Tale, perhaps. Hamlet is always up there…

Do you have plans to adapt more of Shakespeare’s plays into a novel? If you do, or if you would, which play would you choose? If not, why stop here?

We’re talking about it. The book seems to be doing really well, but it will be a few months before we can properly assess its success and that will indicate whether listeners want us to do another. David and I are both very busy right now, but I wouldn’t be surprised if we do this again in a year or so.

What has the reaction been to the audiobook? Have other Shakespearean scholars been supportive or critical?

All the Shakespeareans I know have been very supportive though there are probably some who really hate the idea. They are unlikely to tell me so. Mainstream critical response has been very positive, and the book seems to be selling extremely well. Better than I expected. I thought the very association with Shakespeare might be a turn off. Apparently not.

Can you tell us a little about the “Shakespeare in Action Center”, and your involvement with it?

The Centre is an interdisciplinary group of scholars at UNC Charlotte dedicated to public events exploring Shakespeare in performance and culture. We host speakers, mount productions, arrange colloquia and generally try to engage a broad public in Shakespeare-related debates that have artistic and intellectual depth. Right now we’re in the midst of our 36-in-6 project in which we stage one event for each play (give or take) on the 6 years approaching the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death (April 2016).

What are you working on right now?

Currently finishing the edits to my second middle grades adventure, the first of which, Darwen Arkwright and the Peregrine Pact, comes out from Penguin/Razorbill in October of this year. I’m also finishing academic books on Julius Caesar in performance and on Shakespeare and political theatre.

Who, or what, is your greatest inspiration as a writer? What about them inspires you?

Probably Shakespeare, because he worked in the most popular medium of his day, pleasing people from wildly different sections of society while producing the richest, most complex writing in the language. Tough act to follow.

Where can people purchase Macbeth: A Novel?

From Audible.com or Amazon.com.

A.J. Hartley is currently featured on DarkMediaCity, a free social network for those who like it Dark. Whether it be literature or film, music or art, horror or sci-fi, paranormal romance or paranormal investigation, we’ve got something for you. www.DarkMediaCity.com

He can also be found at his website: ajhartley.net

(All interviews are the exclusive property of DarkMedia, and may not be reproduced or shared without permission, excepting links to the interview.)

![West Forest [Short Fiction]](https://darkmediaonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/black-and-white-forest-wallpaper.jpg)

1 Comment