by John Knott:

From March 10th to March 17th, DarkMedia.com and SCREAM Horror Magazine are offering not only a free preview of one of their upcoming articles, “Ninety Years of the Vampire”, but a chance to WIN one of three free copies of the entire magazine!

From March 10th to March 17th, DarkMedia.com and SCREAM Horror Magazine are offering not only a free preview of one of their upcoming articles, “Ninety Years of the Vampire”, but a chance to WIN one of three free copies of the entire magazine!

Contest Requirements:

- Follow @DarkMediaOnline and @ScreamHorrorMag on Twitter

- Tweet “I’ve just entered to win a copy of @ScreamHorrorMag from @DarkMediaOnline“

That’s it!

Contest closes at Midnight (PST) on March 17th. Good luck!

March this year will see F.W.Marnau’s expressionist nightmare Nosferatu (1922) celebrate its ninetieth birthday. Timelessly creepy, Nosferatu also happens to be the oldest surviving example of one of horrors most enduring genres: The vampire movie. With adolescent hordes filling multiplexes to catch the closing parts of the Twilight saga, one could be forgiven for thinking vampires have had a bit of a resurgence of late. But the truth is they’ve never really been away. The public face of the undead may have transformed from Max Schreck’s animalistic Count Orlok into Robert Pattinson’s poster-friendly Edward Cullen, but vampires have been a mainstay of the horror film industry for much of the intervening ninety years. But how did this transformation come about? How did a genre born in the scary world of German expressionism turn into something that one could not honestly describe as being a horror film at all? And just when did vampires start being the good guys? The answer, it would appear, is all to do with those natural bedfellows, sex and horror. In fact, truth be told, it has rather more to do with sex.

Nosferatu (1922)

Although the vampire’s origins lie in folklore, it was during the nineteenth century that they became a literary genre. It was the likes of John William Polidori, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu and, of course, Bram Stoker who gave us our popular notion of what vampires are all about. Stoker’s Dracula with its vampire hunters, blood transfusions and phonograph diaries (all hi-tech stuff in 1897) was a sort of Michael Crichton novel of its day but it also featured psycho-sexual themes common to all vampire literature of the time. While the act of biting and sucking had obvious sexual overtones, Dracula’s victims were transformed; their ‘purity turned to voluptuous wantonness’. When Lucy Westenra is turned into a vampire she is released from her fallen state by her fiancé, impaling her with a metaphorically unsubtle stake. Dracula compels Mina Harker to drink his blood from his breast ‘like a child forcing a kitten’s nose into a saucer of milk’ in a scene that must have been genuinely shocking at the time. As odd as it might seem to us now, the sexual subtexts of these stories were a major part of the fear factor for the Victorian reader. In the harsh world of the nineteenth century, anything that threatened familial bonds was actually genuinely frightening and nothing threatens familial bonds like sex; a common theme in Victorian art. A wanton woman was a fallen woman and at a time when it was all but impossible for a woman to support herself without reverting to crime or prostitution, a fallen woman was in a world of trouble. In Le Fanu’s 1872 novella Carmilla, the heroine is stalked by a female vampire; if eroticism was scary then homoeroticism was doubly so. And all this wantonness was also a threat to the men’s ability to keep to the straight and narrow as Jonathan Harker discovers when he encounters the Count’s voluptuous brides at his Transylvanian castle. This was very much horror with a message. It is no surprise that the vivacious Lucy with her many suitors becomes Dracula’s victim while the strong willed Mina, utterly dedicated to one man, ultimately helps in the Count’s destruction. Bad girls will meet a sticky end; best settle down before it’s too late.

It was just twenty-five years after Dracula’s publication that F.W. Furnau produced a thinly disguised silent film adaptation, Nosferatu (1922), without the permission of the Stoker estate. Nosferatu is a scary film; a very scary film. Working with occult artist Albin Grau, Furnau produced a film that terrified its audience at the time but perhaps the most remarkable quality of Nosferatu is its ability to put the willies up audiences to this day. Old horror movies can seem creaky or camp to our jaded twenty-first century palette but the distorted reality embraced by the German expressionist school keeps Nosferatu a profoundly unsettling experience. Count Orlok’s shadow climbing the stairs and reaching for the door remains one of the most influential scenes in cinema, while the iconic moment that he rises like an impossible car park barrier from his coffin in the ship’s hold is an image that is still quite likely to cause a few nightmares. Nosferatu echoed much of the sexual themes of the nineteenth century novels: There are hints of homoeroticism in the interaction between Hutter and Orlok, and when Ellen gives herself willingly to the Count to ensure that his prolonged feeding traps and destroys him in the first light of dawn (an idea first introduced by Nosferatu) there are clear sexual overtones. However, Furnau included this content for very different reasons to those Victorian authors. The sophisticated Berlin audience of 1922 to which Nosferatu premiered could hardly have been more different to the British readers of just a short time earlier. Weimar culture was now established in Germany and Berlin was a hotbed of sexual experimentation; think of the Kit Kat Club in Cabaret (1972) and you’ll get the idea of how different things were. This was an audience that was simply willing to accept this kind of content and be entertained by the sexual threat Orlok represented; a threat made greater by Max Schreck’s utterly repellent appearance as an uncouth rat/spider creation. But Nosferatu is not a sexy film as we would understand it today and Orlok would be very different to the cinematic vampires that would follow.

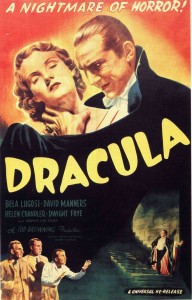

Dracula (1931)

Nosferatu would not have a huge impact at the time if only because litigations by the Stoker estate led to most of the film stock being destroyed shortly after its release. However, nine years later Hollywood made its first foray into the world of vampires with Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931), and the horror film would never be the same again. Universal were taking a big risk as this was also the first of a kind; no-one had ever made a horror ‘talkie’ before and no-one was quite sure what an audience would make of one. But the film was a huge success; audience members fainted at its sheer horror (according to studio coordinated press reports) and talking slowly in a Hungarian accent became, briefly, the epitome of terror. Whilst it does not stand up today as well as Nosferatu, it is nevertheless Dracula upon which the genre would be based; its cultural impact far outweighing its quality as a movie. Principally, it was the exotic and unearthly presence of its star Bela Lugosi that was behind that impact. Lugosi’s performance as the Count gave us one of the most iconic images in cinema; ask someone to imagine a vampire today and the chances are that they’ll think of a man on his way to the opera. Lugosi became one the most impersonated figures of the twentieth century and, sadly, his career never recovered from the inevitable typecasting (even though he was only ever to play Dracula himself on screen one more time). Lugosi’s vision of the vampire as a courtly and urbane nobleman was to become the standard industry model for some time.

Although sex is not entirely absent from Dracula, be it Lugosi cruising the London streets, his cloak wrapping round his victim, or Helen Chandler’s Mina becoming just a little bit sexier in manner and dress as soon as the Count starts his nightly visits, it must be said that the whole sexual subtext is very much downplayed. This is possibly explained by the increasingly interested censors of the time but it still leaves Dracula as an exception among the genre. But five years later Dracula’s Daughter (1936) was released and for the first time a female vampire would take a central role. Furthermore, the film would gain some notoriety with the resurrection of lesbian themes not seen in the genre since Le Fanu’s Carmilla. Historical evidence would suggest that not everyone picked up on its lesbian overtones but the tagline ‘save the women of London from Dracula’s Daughter’ would seem to suggest that the studio had rather hoped they did. Viewing it now it is hard to believe that anyone missed it; Countess Zaleska cruises the streets and picks up young girls to model for her, then seduces and attacks them back in her studio as soon as they start to remove their clothing. The fact that the plot involves Zaleska trying to find a cure for her vampirism has led some observers to comment that a parallel was being made with lesbianism as an illness (this was the 1930s, after all). However, this is a film that features a Billy Bevan comedy routine; this is a film that was nothing more than a crowd-pleaser. The inclusion of these scenes was to put bums on seats. Lesbianism is not the threat it was in nineteenth century literary works; as the tagline suggests, this was titillation being used in an attempt to repeat the box-office success of its predecessor. But Dracula had already been eclipsed by the Frankenstein films and soon vampires were to become over familiar with the public.

Bela Lugosi as Dracula

Despite appearing as a vampire in Browning’s Mark of the Vampire (1935) and The Return of the Vampire (1944), Lugosi was to play Dracula just one more time in the comedy Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948) as the Universal horror cycle limped to an end. Humour had already become part of the show with the Billy Bevan routine reappearing in The Return of the Vampire (this time as a comedy ARP warden rather than a policeman) and with the typecast Lugosi seen somewhat as a self-caricature, it was perhaps no surprise that Dracula should bow out with Abbott and Costello. The fact that it was Frankenstein who made it into the film’s title just added insult to injury. The truth was that with the onset of the Cold War, traditional horror monsters just couldn’t compete. How could Dracula, Frankenstein, the Wolfman or the Mummy possibly compete with something as real and scary as the power of the atom? Especially true when one considers no-one really understood what the power of the atom actually was. For some reason it became the generally accepted truth that until it got around to bringing about Armageddon, the H-bomb was quite likely to spend the intervening time making nature very big and dangerous and/or release long extinct creatures from million year old blocks of ice. As a result Hollywood’s horror monsters were replaced by the likes of giant ants in Them! (1954) or the (entirely made up) Rhedosaurus in The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953). Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend at least gave the vampire an apocalyptic twist (everyone in the world except the hero had succumbed to vampirism) but it would not be until the 1960s that it would make it into film as The Last Man on Earth (1964).

The Curse of Frankenstein (1957)

But on the other side of the Atlantic in drab 1950s Britain, something was afoot. As it emerged from post-war austerity, the British film industry was in the doldrums. Hammer studios had experimented with the newly popular sci-fi but, despite the success of The Quatermass Xperiment (1955) and X the Unknown (1956) it couldn’t realistically compete with Hollywood’s budgets to produce the really big monsters required. But those X’s in the titles were there for a reason. While most studios were wary of attracting the recently introduced X certificate, Hammer were canny enough to realise that this could actually be used as a selling point. At that time the X certificate limited the audience to 16 year olds and over. Hammer theorized that the almost illicit thrill that the X implied would attract young adults and teenagers. These ‘teenagers’ were a new innovation of the 1950s and represented a whole new source of revenue to the cash-strapped British studios if only someone had the wherewithal to get them into the local fleapits in sufficient numbers. If sci-fi was out then perhaps it was time to return to the horror that had proved so successful for Universal in the 1930s. And so with The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) the world was given its first ‘Hammer Horror’.

The attentions of lawyers had meant that Hammer had to distance themselves from the Universal films’ content but they also ripped up the rulebook for style. Hammer’s horror output had none of the dreamlike quality of the earlier films; they were pacey, visceral and they were in colour. Surprisingly enough, this was quite an innovation for a horror movie and it inevitably meant bucket loads of gore up on the screen. Despite the fact that the critics hated it, Curse was an instant success and even did good business in America. Hammer were clearly going to have to continue to plunder the old Universal back-catalogue and there was never any doubt that Dracula (1958) would be next. Christopher Lee had become a star of sorts when he played the monster in Curse but that was essentially a non-speaking role and one in heavy make-up. But it’s important to remember that this was how he was known to the audience. His appearance at the top of the stairs early on in Dracula is indisputably one of the most important scenes in the history of the vampire movie. After the initial glimpse of his ominous silhouetted figure, our expectations our subverted entirely as he then skips down the stairs to greet Harker in the most polite and perfect English imaginable. He is an unspeakably handsome English gentleman; the dark cloak and all the other tropes of Lugosi’s sophisticated nobleman were still there but this was the vampire as the suave sexual predator. This time there was no disguising the sexual content. Why would there be? This was exactly what Hammer’s target audience were looking for. These were the movies you went on a date to see. Stoker’s idea that the vampire’s victims became wanton was back but there was no moral message here; this was sheer entertainment. Just before Lee makes his inevitable entrance to Lucy’s room, she removes the cross from her neck like a wayward teenage girl; Lee’s sexual magnetism was so great that these were willing victims. Following his visits she appears older and less innocent. Conversely, the older and married Mina seems younger and more energised by the vampire’s nightly visitations; Dracula, it would appear, is providing something her husband cannot. It must also be noted that it was during this film that the Hammer actresses perfected that expression of horror and sexual anticipation that became a trademark of their Dracula movies. When Lucy is inevitably staked by Peter Cushing, his clear effort and misplaced hair reveals it on screen for the first time as the metaphor for intercourse that Stoker had apparently intended. Hammer had perfected the marriage of sex and horror.

Dracula’s closing scene also broke with tradition. Apart from the sheer energy of the performances as Peter Cushing leaps across the room to bring down the curtain and let in the daylight (alright, probably a stuntman), there was Dracula’s disintegration. His crumbling to bones and dust was actually considered too horrifying at the time and was partly cut but it is now part of our audience expectation that a vampire’s demise should always involve something dramatic if not entirely horrifying. The special effects department will almost certainly be involved.

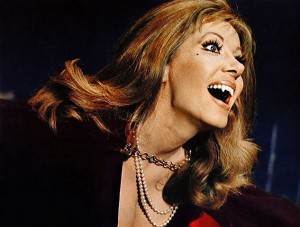

Countess Dracula (1971)

Hammer’s resurrection of the genre continued throughout the sixties with pretty much more of the same formula. But to survive one has to adapt and by the time the seventies arrived Hammer’s output was beginning to look jaded. There was a new permissiveness and cinemas were increasingly relying on pornography to fill seats while the British film industry started to produce alarming numbers of poor quality sex comedies. Hammer’s solution was simply to increase the sex content and make most of their vampires female. If the predatory Lee had been a box office draw, he would have been nothing without his female victims. Therefore, making the vampire protagonists women had to be a winner. Now, there are those film historians that would argue that giving the likes of Ingrid Pitt far meatier roles in films such as Countess Dracula (1971) than she would normally have expected in a Hammer says rather a lot about the rise of feminism at this time. However, Hammer’s Karnstein Trilogy (based very, very loosely on Le Fanu’s Carmilla) depicted lesbian themes fairly explicitly, especially when one considers these were actually supposed to be horror movies. While The Vampire Lovers (1970) featured the threesome of Ingrid Pitt, Madeline Smith and Kate O’Mara, the casual viewer of Lust for a Vampire (1971) could be forgiven for thinking they had stumbled across a soft porn movie. Hammer really pulled the out stops with Twins of Evil (1972) by casting Playboy Playmate twins Mary and Madeline Collinson in the title roles; acting credentials were not required. These were no ground-breaking piece of seventies feminism; they were simply using the nineteenth century themes of sex and lesbianism subverted into entertainment much as Dracula’s Daughter had done thirty-five years earlier; this time with more flesh on show. Hammer was surviving the only way it knew how.

To be fair, Hammer did have one or two other tricks up their sleeve. At the same time that American International Pictures were cashing in on blaxpolitaion movies with their Blacula (1972), Hammer tried to attract the hippies and cool kids by moving things to the (then) present day with Dracula A.D.1972 (1972). Its lack of connection with youth culture (the tag line was ‘he is ready to freak you out’) didn’t stop them trying again with The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1974) and (somewhat unbelievably) trying to get in on the seventies Kung Fu fad with The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974). Satanic Rites requires some further mention here and not just to point out that Christopher Lee, who hated it, was entirely incorrect; it’s actually a classic. Not only did it feature the best basement full of ‘brides’ to ever feature in a movie (the attraction and repulsion are perfectly blended); it also introduced a couple of reasonably fresh ideas. There was the interest of government agents in Dracula’s nefarious activities; not quite a secret organisation of vampire hunters but they had technology of their side and vampires would never be quite so safe again. And then there was also Van Helsing’s curious idea that the reason for Dracula’s world-ending project (it’s something to do with the bubonic plague) is that he has a death wish himself; the Count has just had enough of it all. The idea that even Dracula is so depressed he wants to end it all is perhaps symptomatic of the equally depressed 1970s Britain that produced the film but at the same time the idea that vampires have feelings too was also beginning to take place in the books of American author Anne Rice (or books ‘from the vampire’s point of view’ as The Simpson’s Otto Mann so eloquently puts it).

The Lost Boys (1987)

It wouldn’t be until the nineties that Rice’s books made the transition to celluloid with Interview with the Vampire (1994) but by then studios had caught onto the rise of goth youth-culture and vampires had been turned into young bad boy outsiders in The Lost Boys (1987) and misunderstood romantics in (somewhat ironically) Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). Quite how a vampire who, faithfully to the source material, kills a baby in an early scene could be seen in any way sympathetic is anyone’s guess, but that didn’t stop Francis Ford Coppola (sort of) returning to the genre’s roots and giving them a bit of a new spin. The vampire was no longer a simple villain; they just had different needs and that made them what they were. There was a wave of films like Blade (1998), Underworld (2003) and Ultraviolet (2006) that embraced the genres of action and even sci-fi, but they all featured far more time explaining the vampires’ motives than had ever been the case in the glory days or either Universal or Hammer. The darkly satirical Daybreakers (2009) revisited Richard Matheson’s mass vampirism theme with a consumer driven society of undead facing ever dwindling (literal) human resources. Those who cannot pay for blood become horrific demonised outcasts while the film’s real monsters are an all too familiar greedy corporate elite. This need for clear motivation had by now become part of audience expectation. But the consequence of understanding the bad guys is that they’ll never seem quite so villainous and it was inevitable that some of these films started to cast the vampire as the hero. The misunderstood outsider who means well despite their very nature making them appear as a monster to other people? Is there a teenager in the world who hasn’t thought this describes them perfectly?

Although teenage concerns had been part of the genre since The Lost Boys and Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1992) with its clever twist on the Last Girl theme, the industry finally realised that it was vampirism itself that was the metaphor for teenage angst. Tomas Alfredson’s Let the Right One In (2008) dealt sensitively with the story of an isolated youngster and managed to combine its coming-of-age theme with a darker teenage fantasy of vampire as avenging guardian angel. But later the same year Hollywood released the far more sanitised Twilight (2008), the first adaption of Stephanie Meyer’s blockbusting series of teenage novels. Twilight successfully combined the old sexual themes of the vampire of story with the new themes of outsiders and romance. But while Robert Pattinson’s Edward Cullen is certainly attractive to the target audience, one would be hard pushed to describe him as predatory. In fact, Cullen is quite the opposite and tries to dissuade the heroine from taking the leap to vampirism. His vampiric state means that they cannot even consummate their relationship in the conventional way and their relationship remains chaste. What on Earth is going on? What kind of vampire film is this? It certainly isn’t a horror movie. The truth is that Stephanie Meyer’s source material is, by her own admission, heavily influenced by the author’s devout Mormonism. Therefore it can come as no surprise that the Mormon belief in sexual abstinence before marriage is a theme reflected in her work. The vampire story has come full circle. Victorians used the genre to warn of the consequences of sex; the Twilight saga is doing exactly the same thing. Some observers have noted that even in the steamy days of Hammer it was the good (blonde) girls who survived to marry the hero while the bad (brunette) girls who succumbed to appetite of the vampire. So what has changed? The difference is that the Victorians were using the genre as horror and trying to put the fear of god into their audience. Hammer just wanted to entertain you. Twilight is simply a romance; a gentle guiding hand to its largely teenage fan base. It acknowledges that, rather sadly, vampires just aren’t that frightening anymore.

Max Schreck as Count Orlok

Will vampires ever return to their horror roots? Will they ever be truly scary again? One could easily see the current popularity of the zombie movie losing its edge to over familiarity (if it hasn’t already) so perhaps there is just an inevitability to all this. The vampire is as popular now as it has ever been but with Twilight’s romantic leanings and Underworld’s sci-fi action credentials it doesn’t look like the mainstream vampire will truly be scaring anyone anytime soon. As long as the vampire can fill a multiplex, why should they need to frighten anyone? Let the Right One In did at least remind us that the vampire story can still be creepy and successful; perhaps some young visionary can embrace the ninety year old spirit of Nosferatu and scare us all over again.

SCREAM Horror Magazine can be found on their website and on Twitter @ScreamHorrorMag.

From March 10th to March 17th, DarkMedia.com and SCREAM Horror Magazine are offering not only a free preview of one of their upcoming articles, “Ninety Years of the Vampire”, but a chance to WIN one of three free copies of the entire magazine!

From March 10th to March 17th, DarkMedia.com and SCREAM Horror Magazine are offering not only a free preview of one of their upcoming articles, “Ninety Years of the Vampire”, but a chance to WIN one of three free copies of the entire magazine!

Contest Requirements:

- Follow @DarkMediaOnline and @ScreamHorrorMag on Twitter

- Tweet “I’ve just entered to win a copy of @ScreamHorrorMag from @DarkMediaOnline“

That’s it!

Contest closes at Midnight (PST) on March 17th. Good luck!

Comments are closed.