DarkMedia Interviews Jasper Kent:

Jasper Kent was born in Worcestershire, England in 1968. He attended King Edward’s School, Birmingham and went on to study Natural Sciences at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, specialising in physics.

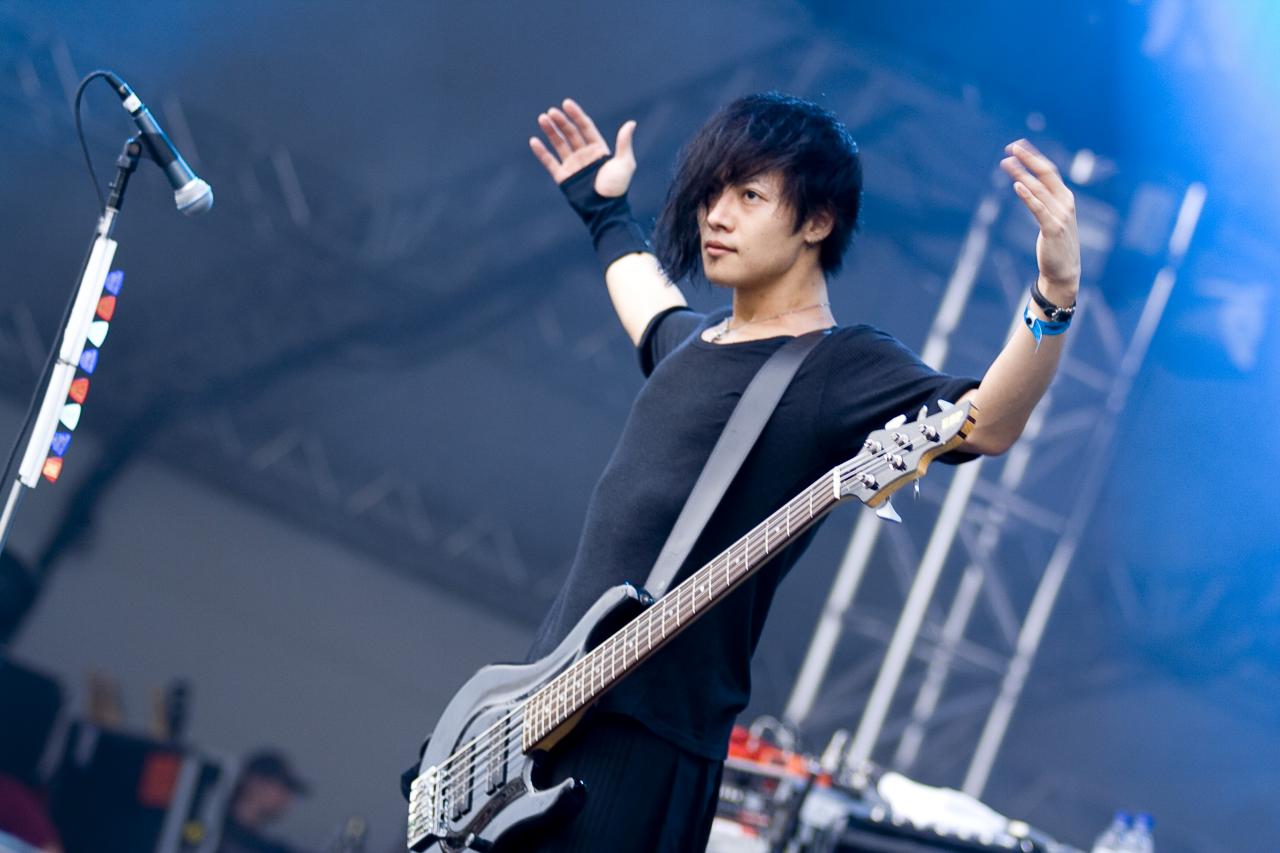

Jasper has spent almost twenty years working as a software engineer in the UK and in Europe, whilst also working on writing both fiction and music. In that time, he has produced the novels Twelve, Thirteen Years Later, Yours Etc., Mr Sunday and Sifr, as well as co-writing several musicals, including The Promised Land and Remember! Remember!

He currently lives in Brighton, with four rats called Nyssa, Isolde, Messalina and Maude, and a person called Helen.

Will you tell us a little about “The Danilov Quintet”? What do your readers have to look forward to?

The Danilov Quintet is an epic family saga spanning a century of Russian history. It begins with the exploits of Aleksei Ivanovich Danilov during Napoleon’s invasion of 1812 and ends with the Russian Revolution of 1917. Along the way, Aleksei and his offspring find their lives entangled with the Russian royal family – the Romanovs – and with pact made between a tsar and a monster a century before our story begins. And if that’s not enough, the monster in question was a voordalak – a vampire – a creature that has walked the earth for centuries and vowed vengeance upon the Romanov family throughout the generations.

You’ve created such a rich atmosphere in your work; the setting plays as large a part in your stories as the characters themselves. Can you tell us a little about your process? How much time do you spend on historical/geographical research versus plot, and how do you weave the two together as you write?

The research – both geographical and historical – is a massive piece of work before I ever start writing or even plotting. The two are important in different ways. Historical events structure the whole narrative; I’m not trying to write stories that simply take place in a particular period, but ones which are inextricably entwined with events. At an early stage I’ll write out a calendar of what happened historically, and then build on to it the story I want to tell.

Geography is generally less constricting; on a broad scale the plot rarely hangs on a particular building being in a particular place (though having said that, I think Thirteen Years Later would have been a very different book if the cave city of Chufut Kalye hadn’t existed). On the whole, geography is much more about atmosphere and verisimilitude. When I first visited Moscow, after I’d done the main bulk of the writing for Twelve, I felt immediately familiar with the city thanks to the hours and days I’d spent poring over maps both old and new and in my mind walking alongside Aleksei through the streets. Hopefully that feeling of familiarity seeps in to the text and gives the reader the same sense of knowing the locations where the story takes place.

My starting point was that I wanted my vampires to be indisputably the bad guys; that was very much a reaction to (though not a criticism of) a lot of recent literature which looks at vampires in a different way. I wanted to get back to the monsters of my childhood.In a previous interview, you said, “I think every author is pretty much free to reinvent vampires as he or she sees them.” How do you see vampires, and how has that interpretation influenced your “reinvention” of the vampire in Twelve?

My starting point was that I wanted my vampires to be indisputably the bad guys; that was very much a reaction to (though not a criticism of) a lot of recent literature which looks at vampires in a different way. I wanted to get back to the monsters of my childhood. It turns out that that’s tricky to keep going – and to keep interesting – over five books, so I have to invent new ways for them to be bad. The point I was making about reinvention was (I think) in terms of specific physical characteristics such as reaction to religious symbols, exposure to sunlight and so on. Any author can pick and choose from the broad palette available, and even invent their own characteristics. The problem with reinvention is you can only do it once. I reinvented vampires for Twelve, but thereon in I have stick to my own rules.

Would you call your vampires heroes or monsters? Is it ever really that simple?

My deliberate intent in Twelve was to really make it that simple and to make them monsters. As I mentioned above, that’s a difficult simplicity to maintain over five books, but it’s a theme on which there is plenty of room for variation.

The French invasion of Russia in 1812, and its aftermath, played a significant role in Tolstoy’s “War and Peace”. Did his account of the events and the effect it had on the people of Russia play a part in your own research and interpretation?

I don’t think you could write any book about the period without being influenced by War and Peace. To be honest, I don’t think an author who’s read the novel could write anything at all without being influenced by it. There’s much in Twelve particularly and in later books that directly references Tolstoy (as well as plenty from Dostoevsky and others). One thing I came across during research was that Tolstoy’s original plan was to write a series of novels covering the Napoleonic invasion, the Decembrist Uprising of 1825, and the return of the Decembrist exiles in 1856. In the end, his plan changed, but that’s basically the path that the first three books of the Danilov Quintet follow.I don’t think you could write any book about the period without being influenced by War and Peace. To be honest, I don’t think an author who’s read the novel could write anything at all without being influenced by it.

How closely does your vision of the legendary voordalak follow the examples given in “Isis Unveiled”? Can you tell us a little about the legend itself?

As mentioned above, the voordalaki are simply my own take on vampires based on the various Slavonic myths and their later interpretations by mostly western authors. There’s no real attempt to be true to any particular legend; having trammelled myself with the need to be historically accurate, I felt it was only fair to give myself some leeway regarding legend.

What’s your favorite book to give as a gift, and why?

That would always depend on who the gift was for. I can’t think of many books I’ve given to more than one person. It’s not always wisest to give what you really want for yourself, although last Christmas my girlfriend and I unwittingly gave each other precisely the same book as a present: Inside the Wicker Man by Allan Brown.

What are you reading right now?

The Three Musketeers by Alexandre Dumas.

What advice would you give to aspiring authors? What’s the best, or worst, advice someone gave you?

As someone who’s only been writing seriously for a few years, I’m disinclined to either give or take advice. Everybody’s path to writing is going to be different. If there was one thing I’d say, it’s get a proper job as well – both so that you don’t starve, but also so you gain a far wider experience of human behaviour than you’ll get purely from social contact. In terms of the best or worst advice I’ve received, it’s still a bit early to say what’s been good and what’s been bad.

How can your readers support you and your upcoming projects?

Well, obviously keep buying the books. You can visit my blog, or my website. Probably the most interactive forum is on Facebook, so do go there and become a fan. Or you could always dress up as a voordalak and wander through your local shopping centre, as did these chaps in Istanbul.

Finally, what’s got you excited or inspired?

On 17th December 2010 a Tunisian street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in protest against constant harassment from government officials. He died 18 days later, but his act precipitated the fall of the governments of Tunisia and Egypt, a civil war in Libya, and other consequences at which we can currently only guess. I wouldn’t want to belittle the human tragedy of all this, but that aside, it really is the sort of stuff that one usually only reads in history books. Events of this significance only occur a few times in a lifetime – the only other comparable time in mine was the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and its aftermath. As someone who writes about history, I find it quite awe-inspiring.

Jasper Kent is currently featured on DarkMediaCity, a free social network for those who like it Dark. Whether it be literature or film, music or art, horror or sci-fi, paranormal romance or paranormal investigation, we’ve got something for you. www.DarkMediaCity.com

More about Jasper, and his work, can also be found at his website.

To purchase Twelve and Thirteen Years Later on Amazon.com, please click here.

Photo by Gideon Fischer @ Elixer Photography, and biography from www.jasperkent.com.

(All interviews are the exclusive property of DarkMedia, and may not be reproduced or shared without permission, excepting links to the interview.)

![West Forest [Short Fiction]](https://darkmediaonline.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/black-and-white-forest-wallpaper.jpg)

Comments are closed.